Videogames at the V&A Museum (#DesignPlayDisrupt): My Thoughts

- Rob Cain

- Feb 9, 2019

- 3 min read

On February 8th 2019, I took a detour to the Victoria and Albert museum in London for its first exhibit dedicated entirely to video games Currently on show until the 24th of February 2019, the attraction details the impact video games have had in popular culture around the world while also outlining aspects of production. The self-titled collection in the northern hall followed three main pillars…

· Design: Insights into the development process on various modern titles, particularly the more story-driven artistic releases.

· Play: Current considerations surrounding gaming from audience to politics and tackling controversial topics.

· Disrupt: All the zany, off-kilter ways game designers play around with interactive entertainment today.

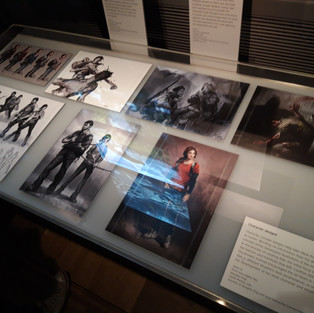

Things started off with several featured games from both the AAA and indie scenes, detailing the design notes that went into each title alongside some details on coding and how they function. The first title on show? Naughty Dog’s The Last of Us; it was a real treat to look over some of the key design documentation behind one of my favourite games from the storyboard for the game’s plot to the motion capture suit worn by Ashley Johnson in cutscene production. Even the AI pathing for Ellie was on show. Other titles included Bloodborne, Splatoon, No Man’s Sky and Kentucky Route Zero; each release was beautifully displayed and gave a unique insight into development that can’t be found anywhere else. More than anything else, it shows how deep and complex modern video games can be and how they have drastically evolved into their modern form.

The second piece of the exhibit was a collection of inputs from current video game designers; with the sheer size and profitability of the industry today, it was inevitable that it would go beyond both Japan and the Western World and start to penetrate other countries around the world, while also entering more adult topics. Aspects of this second pillar will certainly be controversial for some; online discussions can turn highly vitriolic when the topics of inclusivity and politics are brought up. While I feel there have been instances of modern games beating the player over the head to make a point, having these conversations is still important. We’ve seen books, films and even music change and develop over time, tackling subject matters that were once viewed as taboo material. It begs the question; can video games do the same to become a more fledgling part of culture today?

Finally, there was “disrupt” and this stood out as the most strange and random element; because almost any and all age groups are exposed to gaming in some form nowadays, there’s a drive for developers to come up with more experimental approaches to engage people. Wacky arcade games, simplistic multiplayer titles and even a car converted into a driving game brought in from Australia. It was a free-form version of the medium in its purest form, showing how creative games can really be. On top of that, you can play the games yourself. The order of presentation across the three pillars was well-thought out as the exhibition starts off with fully released video games, dives under the surface for thematic conversations and finally strips down the medium to its most basic elements.

Overall, I thought “Videogames” was a great effort; it captures the entrance of the hobby into the mainstream quite well with a strong variety of design drawings, interactive elements and insights into the industry at large. I would have like to have seen a stronger sense of continuity looking at how and why gaming is as big as it is today. 2007 was the year when the medium really started to enter everyone’s lives and in the last twelve years, gaming has evolved from a simple pastime for kids to a gargantuan entertainment juggernaut. Despite this gripe, I highly recommend the exhibit for anyone interested in looking beyond just playing games and engaging with them on a cultural level; getting this kind of recognition from the V&A is a great step forward for the industry.

Comments